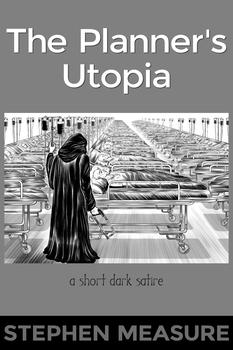

The Planner's Utopia

The planner zealously maintains absolute equality amongst the citizens under his control. But when a free woman invades his warehouse paradise, he must act decisively before she ruins everything.

"It’s better for all to have none than for some to have more."

a short dark satire

Get Ebook:

Included in the short story collection "The Wrong Sort of Stories".

Included in the short story collection "The Wrong Sort of Stories".

Read it here:

The Planner's Utopia

by Stephen Measure

The cardinal soared along the ceiling of the warehouse, red feathers flashing beneath fluorescent light after fluorescent light, the bird’s energy so strange in that silent space. It twisted around perfectly positioned air vents as it flew above precisely aligned gurneys, row upon row of which filled the warehouse; but the cardinal did not notice such things as it flew from one end of the warehouse to the other and back again. It flew because it could. It flew because it wanted to. Such movement. Such beauty. Such freedom.

Its red wings tilted, and the cardinal glided down to rest upon a gurney in the center of the room. Gingerly, it crept forward on the coarse, gray sheet, its small searching eyes examining the shadow below the bald head of the human lying there, the human silent and unmoving. The cardinal had hoped to find food, but there was none; and so the cardinal spread its wings and took to the air again, landing on a gurney a row over, where another silent human lay. But there was no food there either, nothing but a softly breathing human and coarse, gray sheets. The cardinal spread its wings once more, flew, and landed on another gurney, then another, and another, all of them containing a silent human, none of them containing food. The warehouse was perfectly still, perfectly sterile.

The cardinal took to the air again and flew from side to side, searching the ground below it. There! Something next to the wall. Something different. The cardinal swooped down and landed a few feet away. It cocked its head to one side and eyed what lay upon the floor. Then, recognizing the breadcrumbs for the food they were, it bounced forward and grabbed a crumb in its small beak.

A shadow passed above the cardinal, followed by a thud on all sides and then darkness. The cardinal spread its wings to fly but hit something hard right above it. It tried again, only to be blocked once more. Then it stopped, subdued, and waited in the darkness, a darkness that seemed to drag on forever until finally a crack of light appeared on the floor. The crack grew bigger, and a hand reached in and grasped the cardinal, a hand belonging to the planner, who picked the red bird up from underneath the makeshift trap and held it out in front of him.

The bird was really quite beautiful, the planner thought. He hadn’t seen such a vibrant red in years, so different from the grays and browns he was accustomed to in his little slice of paradise.

Imprisoned in the planner’s hand, the bird looked at the planner with eyes uncertain yet empty of fear. It seemed . . . curious. Then it chirped at him. A lovely little sound, which reminded the planner of his youth. He remembered sitting outside beneath the trees in the times before. The bird chirped again. So lovely, the planner thought. He wondered how many citizens could hear it. Citizen #50 and citizen #60 were closest. Certainly they were close enough to hear it, but few others could, which was a pity. If only everyone were able to hear it equally, then it could remain. If only. But like so many things in nature, that was impossible. The bird chirped once more, the beautiful notes stirring something within the planner. But what must be done must be done. He sighed with regret. Then he grasped the bird’s head with his other hand and twisted, snapping its neck.

Silence. Equal silence.

A thrill of satisfaction filled the planner, the same thrill that always came when his actions brought equality. And yet in his mind lingered those two words: if only. He sighed again as he looked at the dead bird in his hand. Such beauty. Such wild, unpredictable beauty. A wild creature could never be allowed inside the warehouse, of course. He knew that, and yet he still felt regret.

If only.

Such a beautiful bird it had been, so full of life, of energy. Its chirping so sweet, so lovely. If only, if only, but no. Its song could never fill the warehouse. Some citizens might hear it, but many would not, and that wouldn’t be fair. That wouldn’t be equal. And, therefore, that couldn’t be permitted.

Everyone must be equal, the planner reminded himself. It’s better for all to have none than for some to have more.

He started toward the utility room to dispose of the dead bird. His feet were padded to mute any noise, and yet he still walked as gently as possible to ensure no citizens could hear him passing. That was as it should be. Why should some citizens get to hear him when others could not? Equal. Perfect. Just as it should be. The bird had not been as it should be. The bird had been wild. It had been unpredictable. It had been uncontrollable. It had been unequal. It had been free. He couldn’t allow a wild creature like that inside the warehouse. Wild creatures—free creatures—are the spawn of nature, and nature doesn’t respect equality. All of the planner’s efforts, all of his work, nature would throw it all away in a moment if the planner let his guard down. How long had the front door been open? Only a minute or two. Just long enough for him to carry the supplies inside. Only a minute or two, but long enough for the bird to fly in, long enough for nature to once again try to destroy the equality he had so carefully cultivated. He had to be diligent. He had to be dependable. The citizens were counting on him, all 116 of them. He was the only thing that stood between them and the ravages of inequality.

Once inside the utility room, the planner opened the small chute to the incinerator. He dropped the dead bird inside and shut the chute. He would have equality. They all would have it. Equality, blessed equality, not the unfair barbarism of nature. He pressed a button and heard the soft whoosh as the incinerator fired up. Nature could try again and again to destroy his perfectly created equality, but he would always be there to stop it. He would always be there to clean up nature’s mess.

He stepped softly back into the warehouse and looked out at the room full of perfectly equal citizens, feeling once again the thrill of satisfaction. How content the citizens must feel, he thought, all of them lying there on their gurneys together, everything perfect, everything equal, nothing to differentiate one from another. Silent, unmoving, equal. It was utopia. It was paradise. And it was all because of him. He was the planner. He made it all possible.

The planner stood there silently, admiring his handiwork, reveling in the satisfaction that was his due. Then, with a flicker, a light on the other side of the warehouse went out, and the planner’s satisfaction vanished as the suddenly dim area marred the perfectly arranged lighting of the room. Panic exploded in his gut. Inequality! He rushed forward, so disturbed that he forgot to tread softly; and in his haste his foot caught on one of the citizen’s IV stands, tripping the planner and almost toppling the IV stand as he fell over.

Calm down, he told himself as he lifted himself up off the floor. You’ll only make things worse if you rush. It can wait a moment. Don’t upset things more by rushing around.

But his guilt spoke to him, as it so often did. It screamed and thrashed inside his mind. Inequality! Inequality! Inequality! Inequality!

Forcing himself to move slowly, the planner scooted the IV stand back to its proper place. Then he lifted the gray sheet away from citizen #92 to examine the citizen’s arm. The IV tube hadn’t come all the way out, thank goodness, but the tape had been pulled from the citizen’s skin, causing a visible abrasion. The planner examined the damage. Well, I’m going to have to settle that, he thought, and he looked around the room at all the citizens in their beds, all 116 of them. He sighed, imagining the work he had ahead of him. But everyone must be equal.

The planner took a small tape measure out of his pocket and measured the size of the abrasion. You’ll never get it exactly right, his guilt told him. But he had to do his best. The citizens were counting on him. He had to do his best. Everyone must be equal.

He memorized the measurement, placed the tape measure back in his pocket, and returned the citizen’s sheet to its proper place. Then, slowly and carefully, he walked toward the site of inequality, which was between citizen #23 and citizen #24. He examined the light fixture above, where one of the fluorescent tubes had gone out and left the two citizens in a slightly dimmer light than the rest. Not a horrible difference, but a difference still the same, and a difference simply wouldn’t do.

At least it’s an easy fix, the planner told himself. He returned to the utility room and retrieved the ladder. Then, carefully navigating between the IV stands and gurneys, he brought it to the site of the inequality, where he left it standing as he went to gather a replacement tube from the supply room.

The supply room was a small entrance room at the front of the warehouse. In times before, this had likely been a reception area, or perhaps a break room. Now he used it to store their supplies. The robot couriers left the deliveries outside the front door, so it made sense to keep the supplies here. That way he wouldn’t have to carry them across the warehouse floor and risk disturbing the perfect equality of the citizens.

He searched through the boxes for the spare light tubes, passing over boxes full of medication, nutrients, spare sheets, catheters, towels, razor blades. Then he found it, a large narrow box labeled “fluorescent tubes.” He set it on the ground and opened it.

It was empty.

Panic exploded once more in the planner’s gut. This was supposed to be an easy fix! He turned the box upside down and shook it. Empty. Empty. Empty. His guilt roused inside of him. No, there must be a spare tube somewhere, he told himself. He hurried over to the unstacked boxes, today’s shipment, which he hadn’t had time to stack yet because the bird had flown in while he was carrying the boxes inside. Frantically, he tore through them. No fluorescent tubes. Why hadn’t he ordered replacements?

And his guilt scolded him. Inequality! What are you going to do about the inequality?

The warehouse wasn’t equal. His paradise had been marred. In desperation, the planner unlocked the front door and looked outside, hoping he had left a box behind in his earlier haste; but there was nothing there, nothing but overgrown vegetation in what had once been a parking lot.

Back inside, he looked through the stacked boxes once more, his hands beginning to twitch.

Inequality! Inequality! Inequality! His guilt was screaming at him.

It’s not so bad, he lied to himself. It’s not such a big difference. He returned to the warehouse to get another look, hoping to be convinced of his lie. He saw the ladder, and there, between citizen #23 and citizen #24, it was noticeably dimmer.

The planner shook his head. We’ll just have to wait, he told himself. He returned to the utility room and logged onto the terminal to request new light tubes. It would be two weeks before the next shipment arrived.

Two weeks! his guilt screamed. How could you let this happen?

It’s not so bad, the planner told himself. Citizen #23 and citizen #24 still have light. Not quite as much as the rest, but it’s not so bad.

You call this equality? You are no better than those before. It’s your fault. The citizens are unequal and it’s all your fault!

But there’s nothing I can do, he reasoned with his guilt. He had no spare light tubes, and the robot couriers wouldn’t return for two more weeks. They wouldn’t come back before it was his turn. That wouldn’t be fair. There were many warehouses to deliver to, many planners to supply.

But what will you do about the inequality?

We’ll just have to wait. It’s not so bad.

That’s a lie! Inequality! Inequality! Inequality!

It’s not so bad. It’s just a little dimmer. The citizens’ eyes are all closed anyway. They probably don’t even notice the difference.

You are no better than those before. Justifications! Reasons! Excuses! You are no better than those before. The citizens are unequal! Look at you, lounging around in your pampered, privileged state. The citizens are unequal and you don’t even care!

Yes, I care, the planner argued with his guilt. I care. I care about equality. I care about everyone having the same.

But his guilt wasn’t listening. Inequality! Inequality! Inequality! it screamed in his mind. Inequality! Inequality! Inequality!

The planner shook with anxiety. How could he have let this happen? His paradise, his utopia—gone, all gone. How could he have let this happen? I do care, he whimpered. I do care.

Then do something, he told himself. Prove that you care.

But there are no spare light tubes, he said to himself. There is nothing I can do.

Yes, there is. There’s more inequality here than just from light.

And then he remembered the abrasion. How could he have forgotten? That was something he could fix. That was something he could make equal!

He hurried back into the warehouse and began his work. It was tricky. He had to rip the tape off each arm in just the right way to give the same size of abrasion. He had to be cautious. If he ripped too much and gave too large of an abrasion, then he would have to go back through all the citizens again.

Everyone must be equal.

It was easier to make a small abrasion first, and then reset the tape and do it again and again until bit by bit it had reached the equal size.

But the color is not the same, his guilt told him. Some abrasions are darker than others. This isn’t equality. You are fooling yourself. Some have more than others. This isn’t equality.

It’s the right measurement, the planner insisted. I’m giving everyone else the same size abrasion. It’s the right measurement. It’s equal. Everyone is equal. Everyone is the same.

Except they weren’t the same, and he knew it. The color of the abrasions really weren’t equal. But that would be impossible! he insisted to himself. He had to focus on the possible. He had to focus on what he could do. But his guilt was right, his guilt was right, his guilt was right—no, he had to focus on the possible. The planner shook the doubts from his mind. He was making the citizens equal. He was. He was making them equal.

And so he went from citizen to citizen, from row to row, working late into the night until he was done. But the thrill of satisfaction at bringing equality did not come to him. He had been so intent on giving everyone the same size abrasion he had almost forgotten the inequality of the lights. But now, realizing he had almost forgotten, he remembered.

You are no better than those before! his guilt reminded him. You let the inequality persist! You let the inequality persist and you do nothing!

There is nothing I can do. I have to wait for new light tubes. There is nothing I can do!

You are no better than those before!

No, I am a planner! I seek social justice! I seek equality!

This is not equality. Some have more than others. This is not equality.

He was exhausted, and there was nothing he could do. Exhausted, so exhausted that he had already started walking back to the utility room to sleep before he realized he had almost forgotten his nightly routine. It was essential that he check the medication levels of all the citizens before he went to bed. If any of them ran out of medication while he was sleeping . . .

Thankfully, no refills were necessary. They would all last until morning. And so, the planner trudged his way back into the utility room, where he pulled the cot down from the wall, lay down, and tried to sleep.

But sleep would not come to him. Not in the midst of so great a failure.

You are no better than those before!

No, I seek social justice! I seek equality!

You are no better than those before. Some have more and you permit it. You are no better than those before!

His breathing became shallow, and he began to rock back and forth on his cot. I can’t give more to those who have less. There is no more to give!

Some have more. That is inequality. That is the very definition of inequality.

But I have no more to give . . .

Then the planner sprang out of bed. The solution was so simple! Why hadn’t he thought of it before? He couldn’t give more to those who had less, but he could take away from those who had more!

His exhaustion erased by excitement, the planner grabbed the ladder and got to work, removing light tube after light tube until every fixture in the entire warehouse had only a single tube. Then, standing on the outskirts of the warehouse floor, he looked out over his dim perfection, and satisfaction filled him once more. It might be hard to see the far end of the room now, but it was equal. He had done it.

It’s better for all to have none than for some to have more, he said to himself. Everyone must be equal.

Yes, he was a planner. Because of him—social justice was possible. Because of him—equality was possible. He was a planner, and today he had defeated one more type of inequality. Once more nature had tried to mar perfection, but he had prevailed against it! He had prevailed, and the citizens were equal once more. Equal once more!

Even his guilt seemed to agree. It was silent as he lay down on his cot; and soon, filled with satisfaction, he fell asleep.

The next morning he was as busy as ever. All of the medications had to be refilled, which was a time-consuming process. This was followed by the necessary airflow and temperature measurements to ensure that nothing had gone awry. The ventilation system had taken months of painstaking work to get right.

And you had tried to take a shortcut! his guilt accused him. You had tried to move the gurneys instead of the vents, ignoring the blatant inequality of the space between the cots!

Yes, but I solved it, the planner replied. Now I just need to keep it solved.

Thankfully, the airflows and temperatures were still perfectly equal, and he was able to move on to the next part of his morning routine: shaving each citizen’s head. He hadn’t always shaved every head. Initially, he had thought that only the males needed shaving. How foolish he had been! It wasn’t until he rescued citizen #56, an old female, that he realized his error. As he had prepped the new citizen for her stay in paradise, he had noticed the bald spot atop her head. What a fool he had been! He had never even considered that hair inequality extended to females, but of course it did—females can go bald as well!

He had found a new source of inequality, something that he had never imagined was a problem before but that now needed to be dealt with decisively. And so, from that day forward, he shaved every head, male and female. The process took twice as long as before. But equality cannot be rushed.

You are no better than those before! Excuses! Justifications!

The planner ignored his guilt at past mistakes. He reminded himself how he had solved the light inequality the night before, the dimness of the room a testament of his success. And the memory brought the satisfaction back, a satisfaction so sweet that he started humming to himself. Not out loud of course—it wouldn’t be fair for some citizens to hear his tune while others could not.

He sat on a small stool as he shaved each citizen, moving from one gurney to the next, humming happily in his head as he carefully cut every hair, not leaving even a trace of stubble. Perfection. Equality.

“Hello?”

The planner froze. Had there been a noise? He looked around the room. It was harder to see now with the light so dim.

“Hello?”

The planner dropped his razor. Had that been a human voice? A human voice?

Nature is always trying to destroy equality!

The planner stood and looked around the room. There was no one there.

“Hello?”

The voice was closer this time. It’s coming from the supply room, the planner realized. He padded softly in that direction. Someone had broken in! How could they . . . oh, no!

He remembered the afternoon before. He remembered his panic and his rush. Had he locked the front door after checking for fluorescent tubes outside? No, he hadn’t. He hadn’t locked it, and now someone had come inside. They threatened everything.

How could you let this happen?

He had to stop them. The citizens were counting on him. He had to stop them before they disturbed the citizens . . .

But it was too late. Before the planner could reach the door, a woman walked into the warehouse. Clad in a mixture of cotton and leather, she had a bow and quiver slung over one shoulder and a pack upon her back. Long red hair fell down around her shoulders, and a large metal trap hung from her pack on one side.

“Hello?” the woman said as she entered the warehouse. Then she stopped, eyes wide.

The planner dropped to his knees and hid behind a gurney. What was he supposed to do now?

She will ruin everything!

The woman walked forward, slowly approaching the nearest gurney. She stood and looked at the citizen who lay there. Then she pulled their sheet down a few inches. The planner trembled at the unbalance she was creating.

Stop her! Stop her! She will ruin everything!

She pulled the sheet back up. But not to the right spot.

Inequality! Inequality! Inequality!

The woman laid her hand on the citizen’s forehead as if feeling for a temperature, and the planner could take the inequality no more. He leapt to his feet and ran toward her. Stop! he tried to whisper. But it had been so long since he had last spoken, his mouth couldn’t form the words. “Stop!” his lips finally managed.

The woman jumped back, one hand reaching instinctively for her bow, but she relaxed when she saw him.

“Oh!” she said, her voice loud enough for an entire section of citizens to hear.

But not the rest! Not the rest!

“I was looking for water,” the woman said as the planner reached her, “and the door was unlocked and I, I . . .” Then she stopped and her hands snapped formally to her sides as she gave a slight bow. “I am called Anaya,” she said, and she stood there, hands tight at her sides, head slightly bowed, as if expecting some action from the planner; but he ignored her, focusing instead on the citizen’s sheet. Just as I feared, he said to himself. She didn’t set it correctly.

“What’s wrong with them?” Anaya asked, dropping her formal stance and moving to stand beside the planner.

“They are sick,” the planner whispered.

“What? I’m sorry, but you need to speak louder. I can’t hear you.”

The planner turned to face her, willing as much volume out of his voice as possible. “They are sick!”

“Oh,” Anaya said. Pity entered her face as she looked down at the citizen once more. “Will they ever get better?”

“They are better now,” the planner told her.

“Now?” Anaya asked. She tried to guess at his meaning. “Oh, you’re saying that they’ll never get better, that they’ll always be like this.” She rested her hand on the citizen’s forehead again, her eyes full of pity.

“Stop that!” the planner snapped at her.

Anaya yanked her hand away. “What? What did I do?” Her eyes grew wide. “Are they contagious?” She took a step back.

“Of course they are,” the planner told her. “They are humans!” He stared at the citizen’s forehead for a moment.

Inequality! Inequality!

“You must touch all their foreheads now,” the planner said. “You touched one. Now you must touch them all.”

“What?” Anaya said. She took another step back. “But you just said they’re contagious! I’m not going to touch any of them!”

“But you must,” the planner insisted. “Otherwise, it wouldn’t be equal.” He returned his attention to the sheet, pulling carefully to align it with the markings on each side of the gurney. Then, the sheets equal once more, he felt the familiar satisfaction fill him, allowing him to forget for a moment the inequality her forehead touching had created.

Anaya brushed a strand of red hair out of her face. “How many are here?” she asked the planner.

“116,” the planner whispered, eyes still on the sheet, double-checking that he had in fact gotten it right.

“116?” Anaya said. “And you care for them all by yourself?”

“Yes,” the planner whispered. “I keep them equal.”

Anaya whistled as she looked around the room. “That’s a lot of work for one person.”

Inequality! Inequality!

The planner whirled toward her. “Stop doing that!” he hissed.

“What?” Anaya asked, confusion on her face. She brushed another red hair away. Her hair seemed to have a mind of its own, so wild, so unpredictable. “I was just saying that that’s a lot of work for one person. Maybe you should get some help.”

They would ruin everything! They would ruin everything!

“No, no, no, no, no, no, no,” the planner said, trembling slightly at the thought. Equality was so precise, so difficult. But that was something he could never explain, so he didn’t even try.

Anaya shifted her pack, the large metal trap jingling with the movement. The planner eyed the trap, and then he looked back at Anaya, who seemed to notice the IVs for the first time. Reaching up, she took the bag of medication and examined it, but the bag was blank. All she could see was the clear liquid inside.

“Does the medication help them?” Anaya asked.

“Yes,” the planner said. “It keeps the sickness away. It keeps them equal.”

“Equal?” Anaya looked around at the rows of motionless bodies.

“Yes, equal. They are all equal here.” Satisfaction swelled within the planner. He stood proudly. “This is utopia. They are all equal here.”

“Utopia?” Anaya laughed at what she thought was a joke.

But the planner did not laugh. He just looked at her, one of his eyes slightly twitching.

“I’m sorry,” Anaya said. “I know you work hard, and I can’t even imagine how exhausting it must be to care for so many sick people, but this is no utopia. It’s clean. I’ll give you that. But I’d take the outside world anytime. Just the silence is enough to drive one batty.”

Silence. Blessed silence. At the mention of the word, the planner realized the gross inequality of sound he was permitting. It was so difficult to regulate sound. Like so many things in nature, it resisted the very idea of equality. Perhaps with a complex system of precisely tuned microphones and speakers—but no, that would be too difficult. Silence would have to do. It’s better for all to have none than for some to have more.

“The water is in the utility room,” the planner whispered to Anaya, and he motioned for her to follow him.

As they walked, he thought of what she had told him, about how she preferred the outside world to his utopia here inside. How could she not see? How could she not understand? This was utopia. This was perfection.

“Things have never been better than they are now,” the planner whispered. He gestured toward the citizens. “Look at them. Has there ever been such equality in all the world? No. In times before, inequality was everywhere. Income inequality . . . all kinds of inequality . . . everywhere, absolutely everywhere!”

Anaya looked at the rows of inert bodies and imagined their muscles atrophying into nothing. Was that even life? Why had they even been born? A shallow grave seemed more meaningful than this. At least then your body would give nutrients back into the earth, which would become flowers, trees, and animals. But this, this was a horror show. She wouldn’t say that to the strange caretaker, of course. That would only hurt his feelings. Besides, he seemed a little mixed up. All this talk about equality like it was the only thing that mattered. And why was the light in here so dim?

“Equality,” the planner continued with his whispering. “Equality is the goal. Equality is everything.”

Anaya stopped and faced him. “Have you ever wondered if maybe you’re focusing on the wrong goal?”

The planner’s eyes narrowed in confusion. “What could be greater than equality?”

“How about freedom?”

“Freedom?” the planner scoffed. “Freedom always ruins the perfection of equality.”

Anaya shook her head. “Equality is a noble goal,” she said, “but freedom must be its foundation. Freedom is greater than equality. If you have freedom without equality, you can use that freedom to achieve the goal of equality. But if you have equality without freedom, you have nothing and you can do nothing. All you have is a sterile hell. Equal? Sure. Equal in nothingness.”

She looked out over the silent humans lying upon the gurneys, and a chill ran down her spine. Imagine lying there, wasting away in perfect equality.

The planner scowled at Anaya. She didn’t understand. Equality was the greatest good and therefore freedom must be the greatest evil. But there was no use discussing it any further. He motioned again for her to follow him, and they continued through the warehouse in silence until they came to the door to the utility room.

“You can leave your pack out here,” he told her. “There is a faucet inside. Take as much water as you wish.” He opened the door for her and stood there waiting patiently.

Anaya shrugged her pack onto the ground, but she kept the bow and quiver on her back. She pulled a large canteen from her pack and then walked through the door into the utility room.

“Thank you,” she told him as she looked around the sparse room. The faucet was on the far wall along with an old terminal. On the wall next to it was a stack of flattened boxes and what appeared to be an incinerator chute. A simple metal cot was attached to the other wall.

“I have something I must attend to,” the planner told her, and the door closed, leaving Anaya alone in the utility room.

What a strange man, she thought. Then she reminded herself how hard it must be to care for so many sick people. 116? What an incredible burden.

She turned on the faucet and stuck her face under the water to drink a few gulps. It was cool and clean. She filled her canteen to the top, and then she took a few more gulps before shutting off the faucet.

This whole place was disturbing. All these sick people, all this silence. And the caretaker, what a strange man. Such weird ideas he had. The solitude must be driving him mad. She wanted nothing more than to gather her pack and get out of this place as soon as possible; yet, seeing the stack of flattened boxes, she couldn’t help feeling a little curious. She examined the labels. Most of them seemed to be food, some sort of processed material, apparently provided via IV. There were a lot of medication boxes as well. The medication’s name was unfamiliar, but there was a description below in tiny letters. She picked up a box and studied it closely. Most of the language was medical jargon, but one word caught her eye: “Sedative.”

Anaya dropped the box and grabbed her bow, an arrow nocked before she even turned around. Now it was clear to her. All those rows of motionless people—of sleeping people. He had told her they were sick. He had told her the medication made them better. Now Anaya knew what sickness he was curing with his medication.

She pushed open the door slowly, her bow drawn tight, an arrow ready to be loosed. Entering the warehouse, she looked out across the prisoners, squinting in the dim light for a sight of their captor. She stepped sideways, her back to the wall, an arrow trained toward the room. She would kill this misguided tyrant, and then she would free his prisoners, and then—

Her left leg exploded in pain as metal spikes drove through her skin, shattering the bone. She screamed and fell to the ground, dropping her bow and grasping the trap that had caught her leg. Her own trap! She pulled at it, but it wouldn’t come loose. The pain was unbearable. Something was held over her mouth and then . . .

* * *

The planner opened the incinerator chute and dropped the last handful of red hair inside. Such a pity, he thought as the fire consumed it. Such lovely hair. If only everyone had been born with such hair, then they could keep it.

If only.

But they hadn’t. Few were blessed with such beauty, and what about the rest? How would that be fair? How would that be equal? If only, if only, but no.

He returned to the gurney of citizen #117 in the warehouse. She looked so different lying there, her head shaved, her eyes closed, her breathing soft. And seeing her lying there in the silence of equality, the planner couldn’t help but feel a little bit of loss. He had seen her walking. He had heard her talking. It was a pity that things had to be this way—yet this was how they had to be. Nature is inherently unequal. Some people are stronger. Some people are faster. Some people are smarter. Some people work harder. You can’t have that and have all results be equal. The solution, then, is to not have that at all.

It’s better for all to have none than for some to have more, the planner said to himself.

Yes, citizen #117 looked very different from before. She looked equal. And the planner felt that familiar thrill of satisfaction. He had done well. The barbarism of nature had been pushed back, and the world had become a little bit more equal. In times before, inequality had been everywhere, but it was a new day now, a new age. And he was part of it. He was part of it and inequality was gone. All of the citizens were perfectly equal.

The planner raised citizen #117’s sheet to examine where her left foot had been. That had been very unfortunate. He had tried and tried, but in the end had been unable to save it. He took out his tape measure and measured how much had been cut off.

Now he had much work to do, much, much work; but satisfaction still swelled inside him, telling him it was all worth it. He hummed a happy tune in his head as he returned the new citizen’s sheet to its proper place, aligning it perfectly on the gurney. Then he stood and carried his medical bag to the next citizen. Pulling the sheet up, he exposed the left leg of citizen #116, measured the necessary length, and marked it precisely on the citizen’s leg. Then he reached into his medical bag and pulled out a saw. He placed the saw carefully on the measured mark and began to cut, red blood pouring down on the coarse, gray sheet.

Everyone must be equal.

Status: Released September 2015 by Silver Layer Publications.

Please share this with others